10 May “My husband fought in the Chaco War” [therefore, why should I pay the opportunity cost gas subsidy?]

You are probably already familiar with gasoline and diesel price subsidies. You likely know that all taxpayers bear their cost. You’ve probably also heard that these subsidies are problematic because the money ultimately comes out of your pocket. But what about subsidies that prevent money from coming into your economy? And I’m not talking about illegal practices, but rather through entirely legitimate fiscal mechanisms. Let me explain.

After several months of work, Marcelo Velázquez and I published a document that reviews the pricing structure of gasoline and diesel in Bolivia since 1986. Additionally, we quantified most types of subsidies in the country. Yes, there’s more than one. The document can be downloaded in this link.

For now, I’d like to focus on two types of subsidies: 1) the direct subsidy on imports and 2) the so-called opportunity cost subsidy. The first is widely known. YPFB buys gasoline and diesel from other countries at high prices and sells them cheaply in Bolivia. To cover the negative gap, YPFB receives notes (NOCREs) from the Government, which it then uses to pay taxes. The result? All taxpayers finance this subsidy. This is a classic case where Bolivians buy at high prices and sell at low ones.

The second type of subsidy is more interesting and less discussed. When you turn on your stove to make coffee or start the engine of your natural gas-powered car, you might think, “This is so cheap.” Perhaps comparing it to the cost of an electric stove or a gasoline-powered vehicle. The reason all Bolivians have access to cheap natural gas—whether for cooking, driving, or electricity—is because the prices paid to natural gas producers are extremely low.

But what exactly is a low price? Is it one that doesn’t cover production costs? One that doesn’t allow producers a reasonable profit? Low compared to what? This is where the concept of opportunity cost —a very economic idea — comes into play. If natural gas producers and YPFB decided to sell this gas to Brazil or Argentina, they would receive prices 7 to 8 times higher. Therefore, when they sell the gas to the domestic market at low prices, they lose the opportunity to sell it in more lucrative markets like Brazil or Argentina.

You might now think, “Well, that’s YPFB’s and the gas producers’ problem. As long as I get cheap gas, I’m happy.” And to a certain extent, you’re right. However, this reasoning doesn’t reflect the full picture. Royalty payments (18%) and the Direct Hydrocarbon Tax (32%) are calculated using this domestic selling price. In other words, when gas is sold cheaply in the domestic market, royalty and tax revenues are also low. Conversely, if this gas were sold on external markets, royalties and tax revenues would be 7 to 8 times higher.

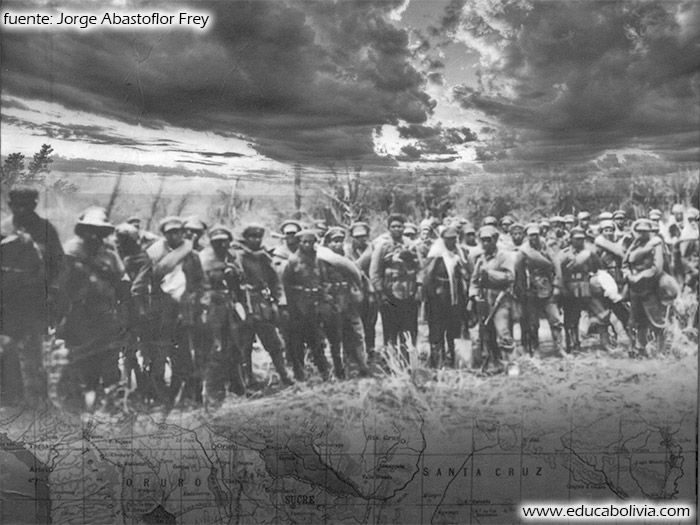

A cold solution would be: Raise domestic gas prices to match the export parity price, the price Brazil and Argentina pay. It’s a tough solution. It reminds me of the time I had to present these concepts at a Human Rights Assembly. A woman raised her hand and said, “My husband fought in the Chaco War defending this gas, so why should I pay high prices for something that is mine?” Simple as that. The lady wants low prices because she considers natural gas to be hers, period.

Everything depends on how the question is framed. What if we asked her: “Would you agree to raise natural gas prices—let’s say, doubling your bill from Bs 10 to Bs 20—in exchange for building a hospital near your home?” Because if we raise prices (eliminating the opportunity cost subsidy), royalties and tax revenues increase, giving national and regional governments more resources to expand public investment. Now, if you believe it’s better to keep prices low rather than letting the State manage these resources, we enter a more complex discussion about how public goods are funded.

In closing, some friends might say, “Mauricio, this discussion is moot because if subsidies aren’t lifted, there won’t be much gas left to subsidize anyway.” Why? Because since 2016, natural gas production has been in steady decline. And yes, they wouldn’t be entirely wrong.

S. Mauricio Medinaceli Monrroy

La Paz

May 10th, 2022

No Comments